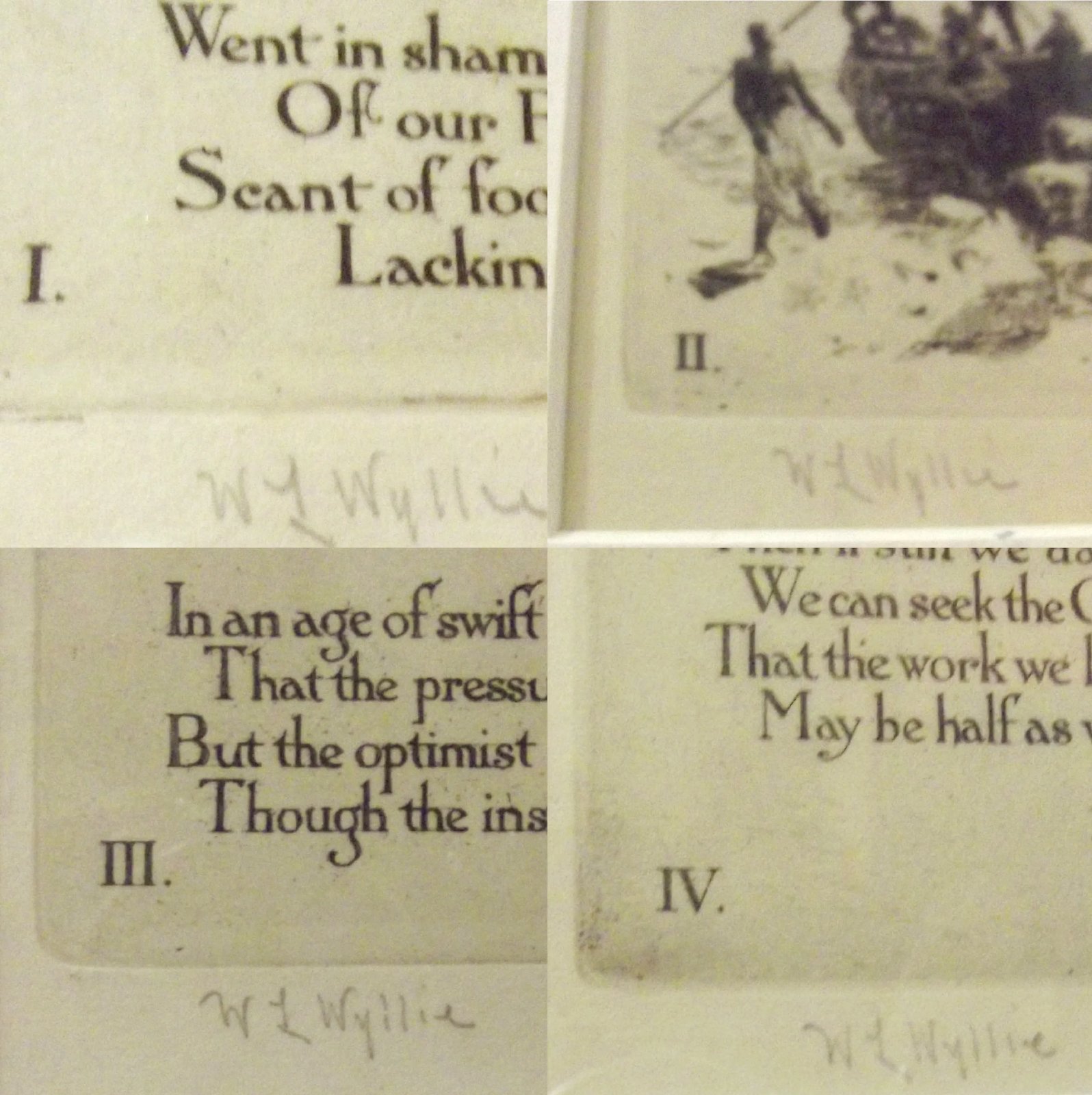

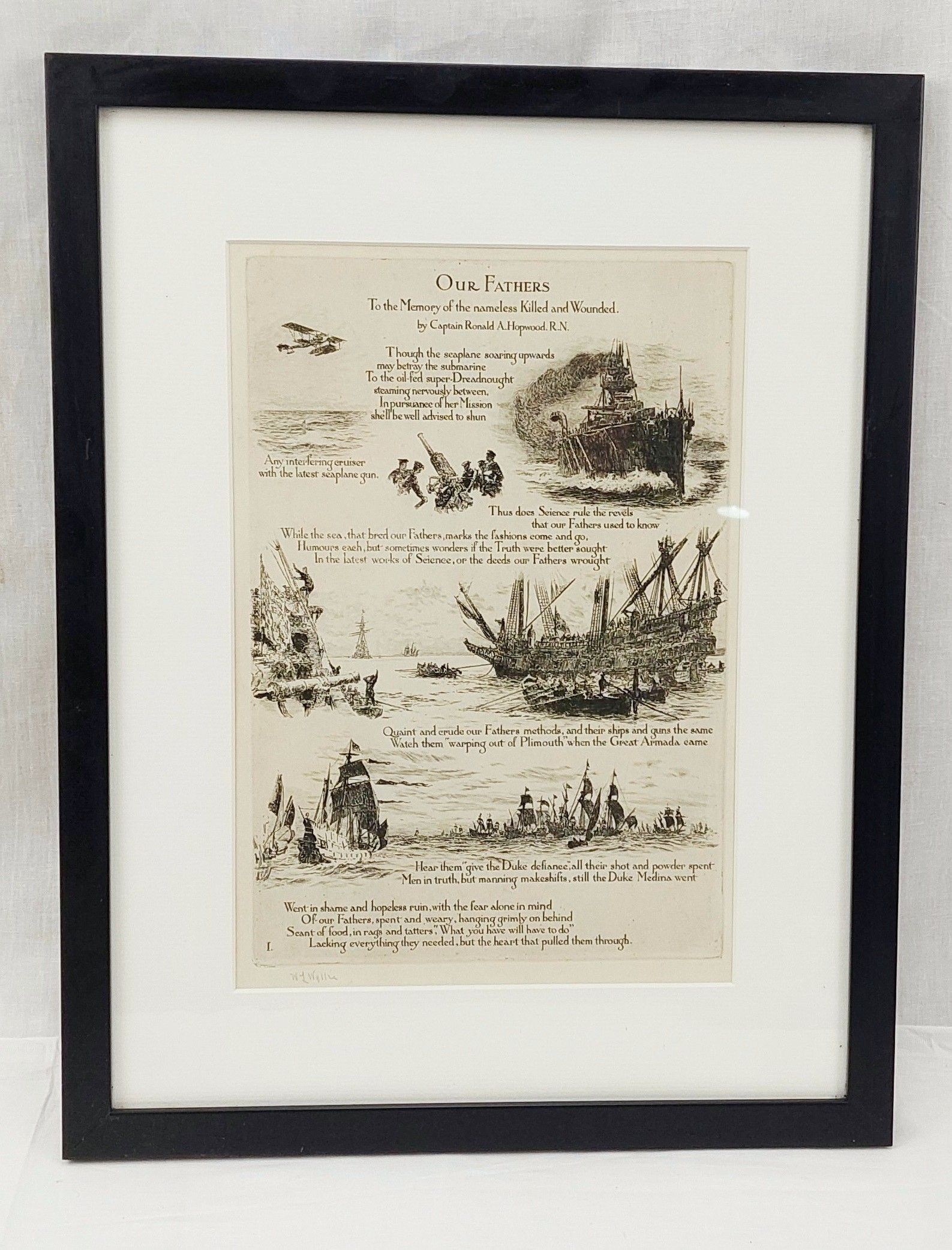

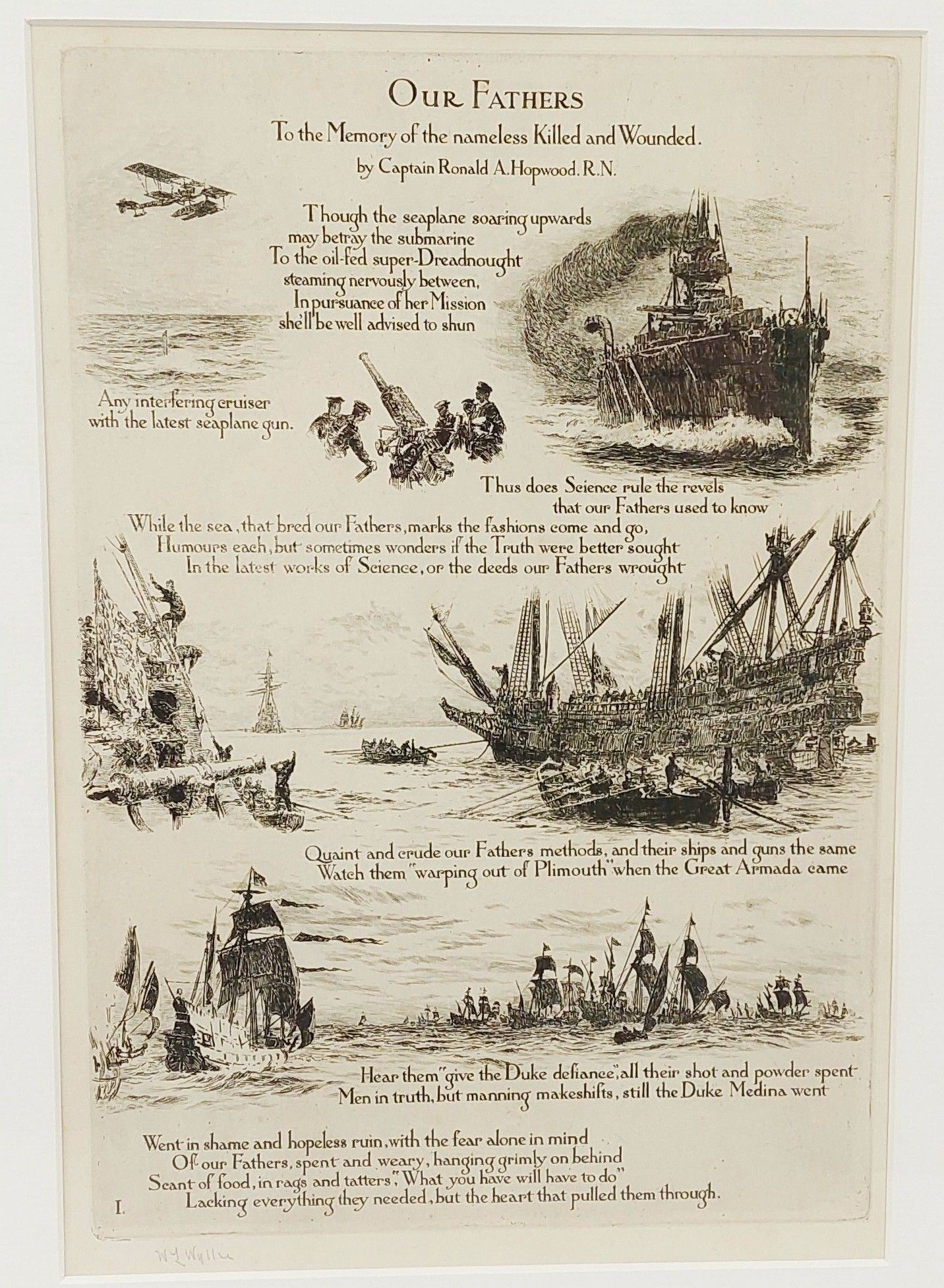

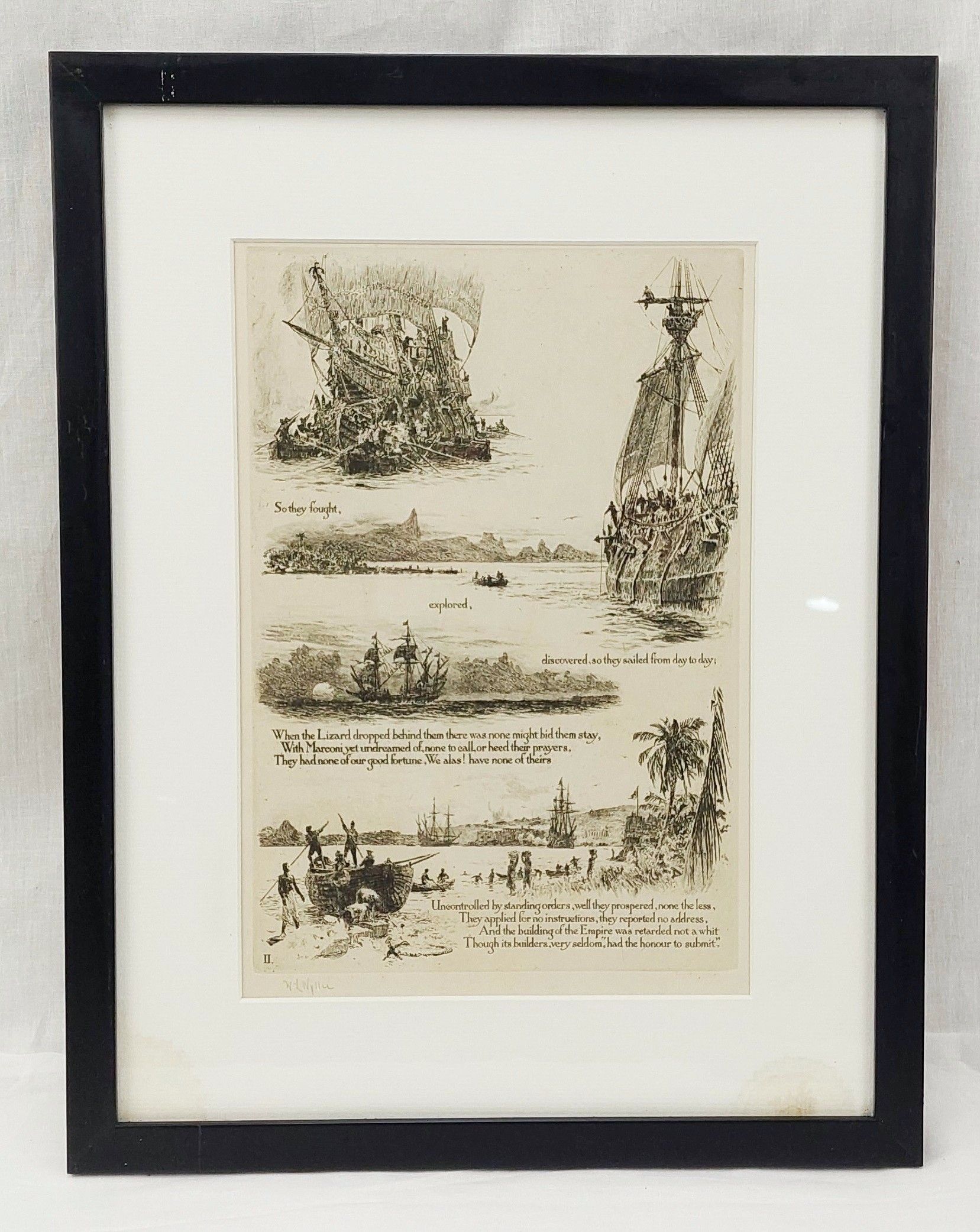

~ William Lionel Wyllie “Our Fathers” Series of 4 Framed Etchings, Signed ~

A set of 4 original, signed, illustrative maritime etchings by the popular and collectable artist W.L.Wyllie.

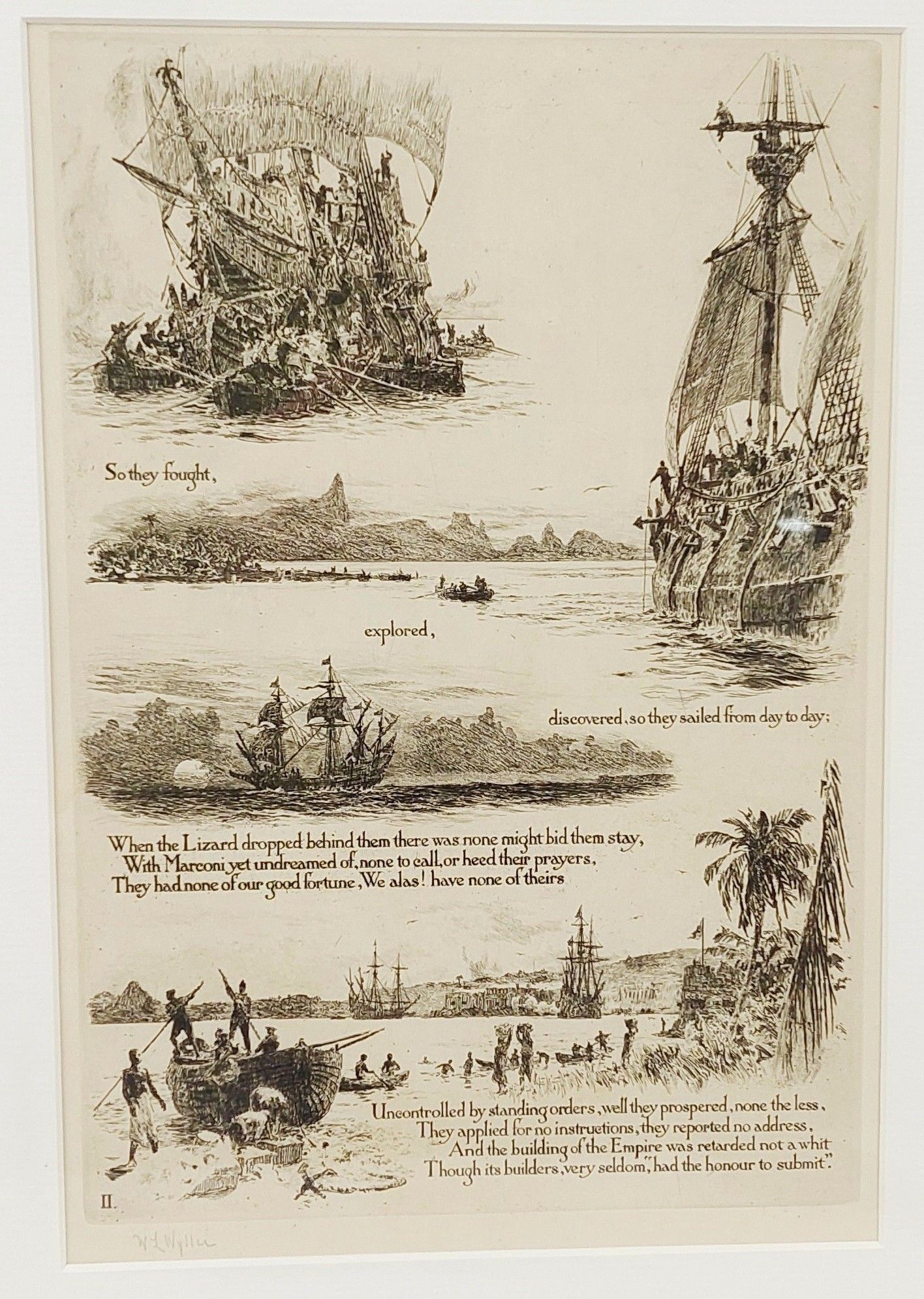

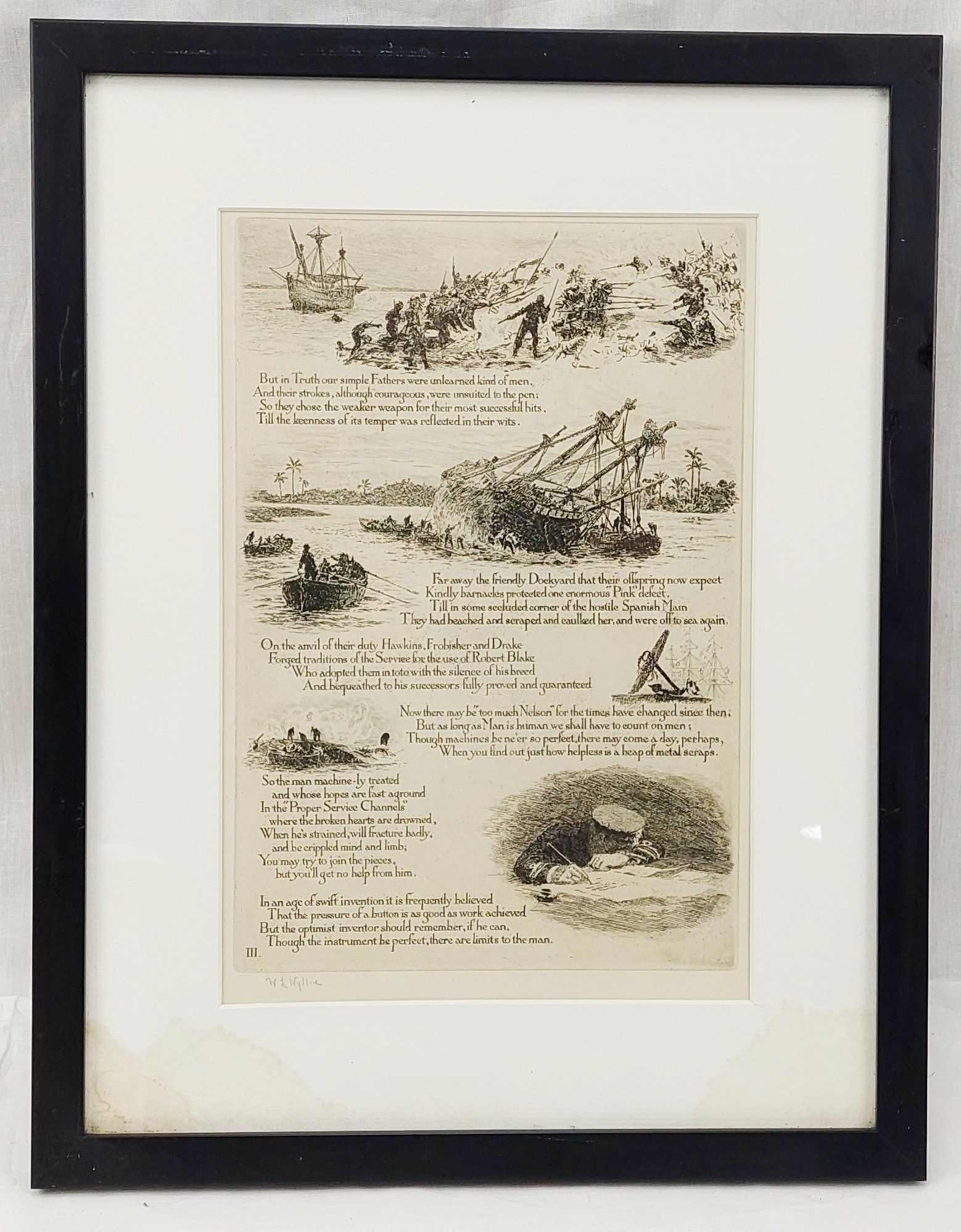

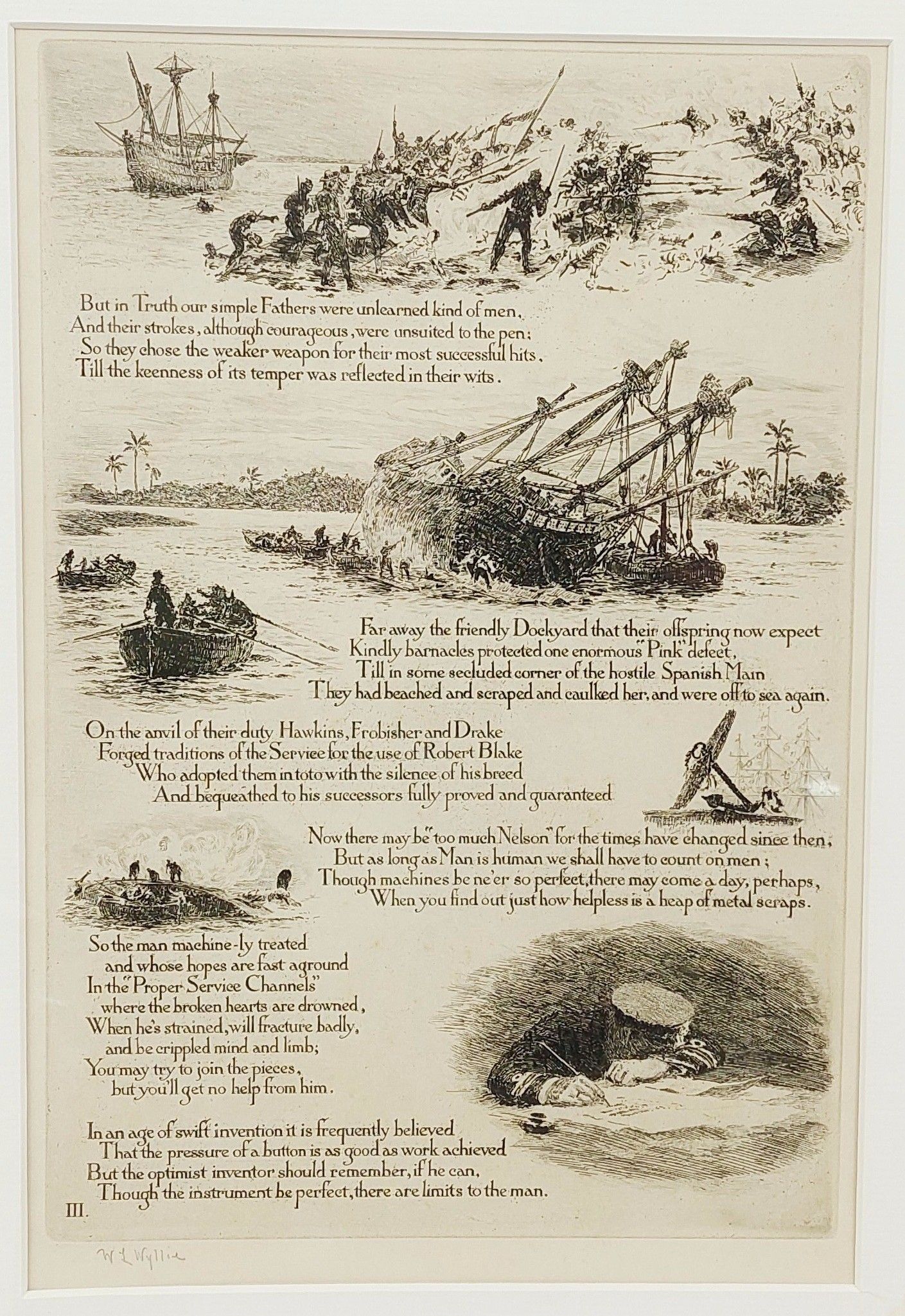

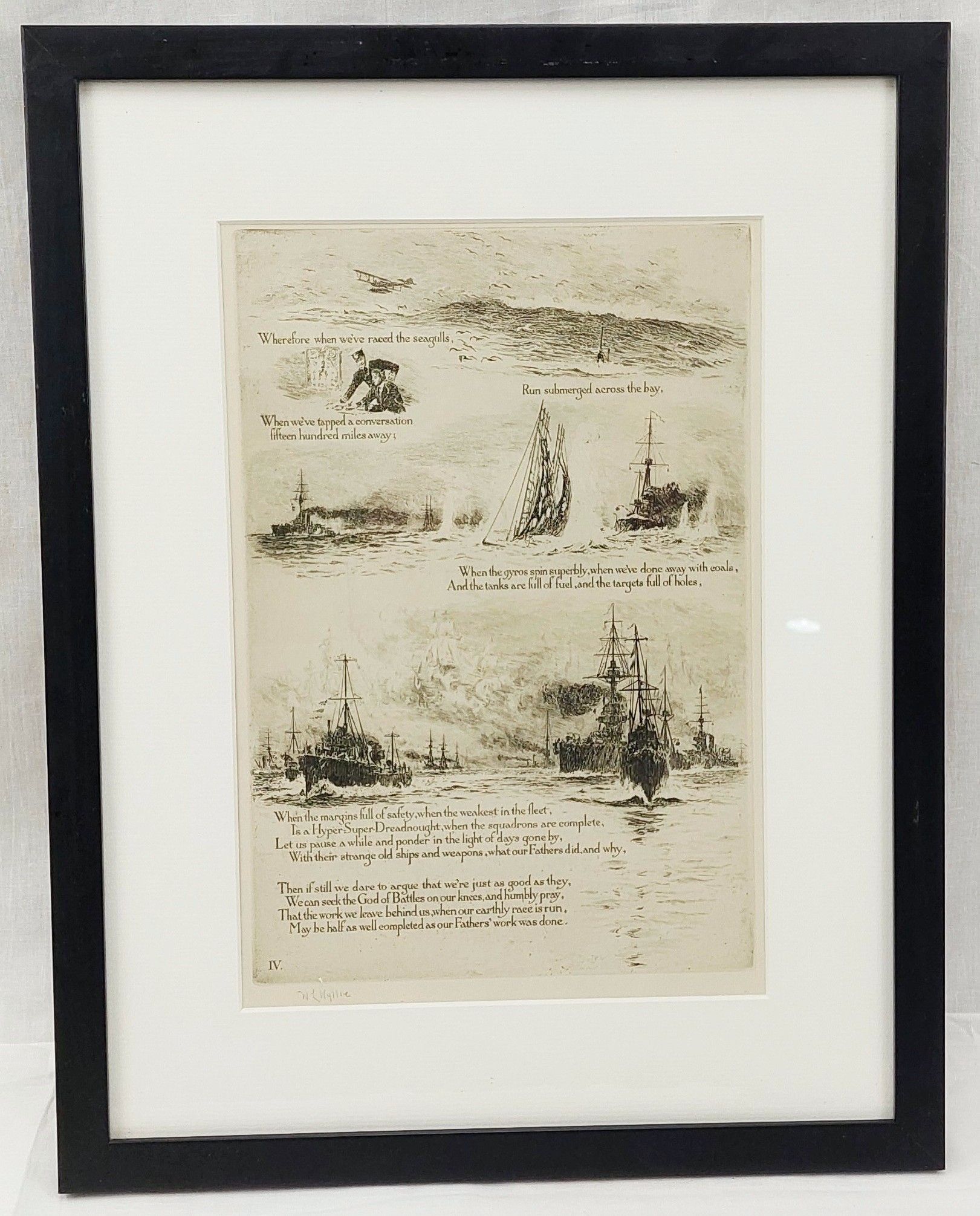

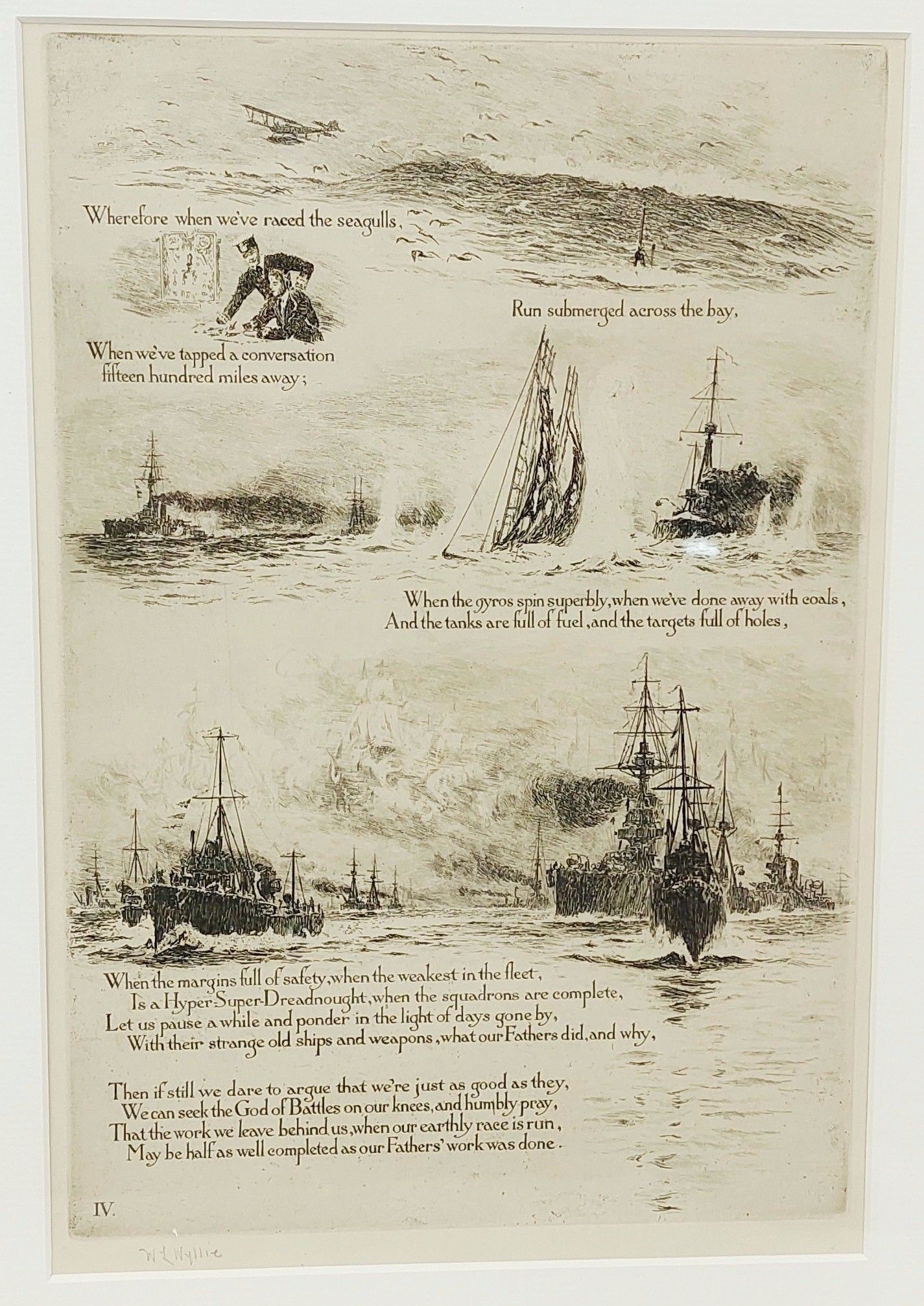

Features “Our Fathers” the emotive titular poem by Captain Hopwood in smart hand drawn script across 4 plates.

~ Dimensions ~

Each frame measures approximately 19 x 14 and a half inches (48 x 37 cm) and the visible print inside the mount measures approximately 13 x 8 and a quarter inches (33 x 21 cm).

Each weighs 1.4 kg (so 5.6 kg in total).

~ Condition ~

The prints are in lovely condition – quite possibly preserved by archival (UV filtering) glass in the frames, they have only ever-so slightly yellowed with age.

Two of the prints have water damage to the mount, though thankfully there is no damage to the actual prints.

The frames are in good order with only light wear.

Please note, any white marks to prints in images are simply light reflection and not marks to prints.

~ Poem by Captain Hopwood ~

THOUGH the seaplane, soaring upward, may betray the submarine

To the oil-fed super-Dreadnought, steaming nervously between;

In pursuance of her mission, she’ll be well advised to shun

Any interfering cruiser with the newest seaplane gun.

Thus does Science rule the revels that our Fathers used to know,

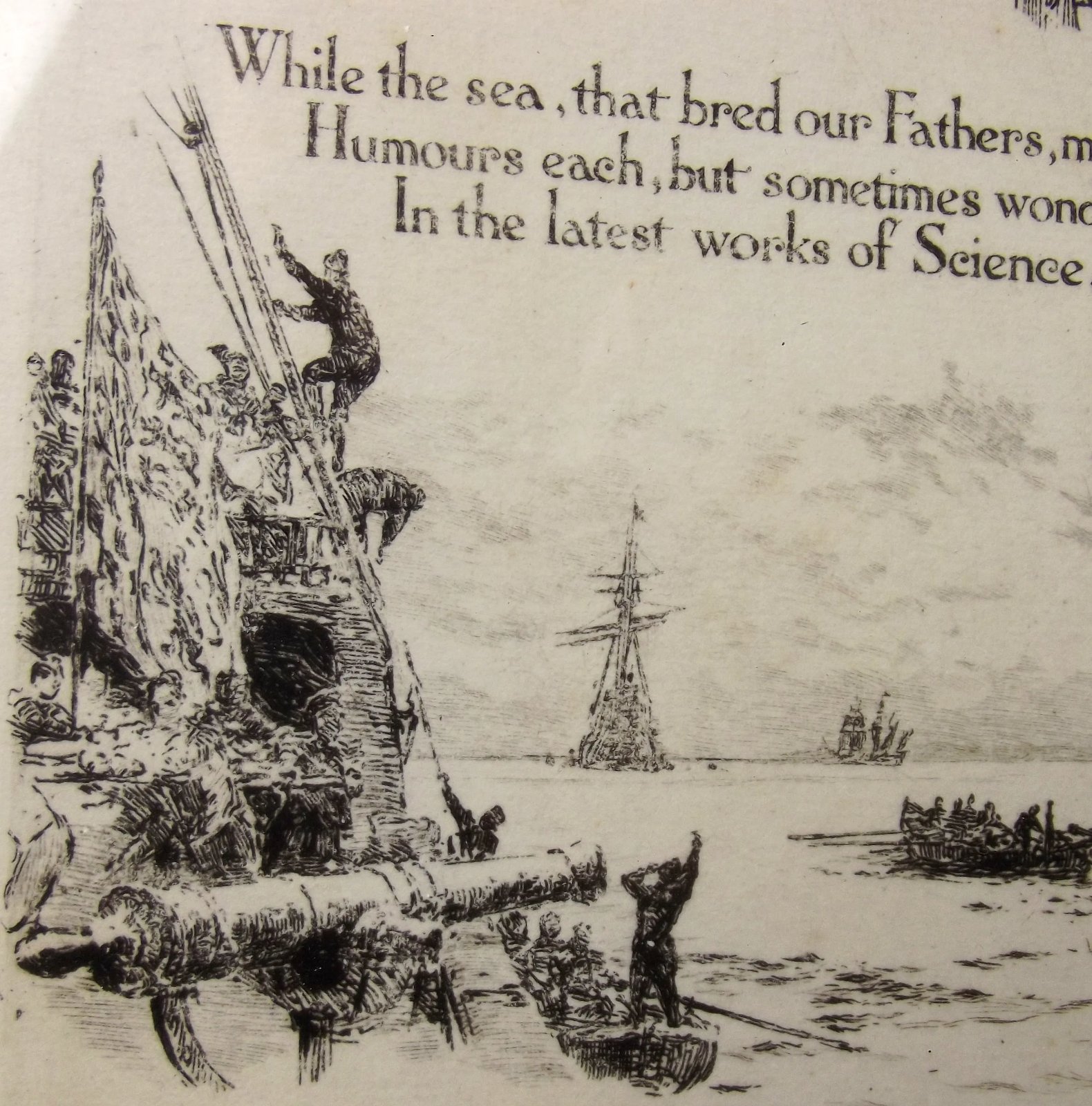

While the sea, that bred our Fathers, marks the fashions come and go,

Humours each, but sometimes wonders if the Truth were better sought

In the latest words of Science, or the deeds our Fathers wrought.

Quaint and crude our Fathers’ methods, and their ships and guns the same;

Watch them “warping out of Plimouth” when the Great Armada came

Hear them “give the Duke defiance,” all their shot and powder spent

Men in truth, but manning makeshifts still the Duke Medina went.

Went in shame and hopeless ruin, with the fear alone in mind,

Of our Fathers, spent and weary, hanging grimly on behind;

Scant of food, in rags and tatters, “What you have will have to do”;

Lacking everything they needed, but the heart that pulled them through.

So they fought, explored, discovered, so they sailed from day to day;

When the Lizard dipped behind them there was none might bid them stay.

With Marconi yet undreamed of, none to call, or heed their prayers,

They had none of our good fortune; we, alas! have none of theirs.

Uncontrolled by standing orders, well they prospered, none the less;

They applied for no instructions, they reported no address,

And the building of the Empire was retarded not a whit,

For its builders, very seldom, “Had the honour to submit.”

But in truth our simple Fathers were unlearned kind of men,

And their strokes, although courageous, were unsuited to the pen;

So they chose the weaker weapon for their most successful hits,

Till the keenness of its temper was reflected in their wits.

Far away the friendly Dockyard that their offspring now expect,

Kindly barnacles protected one enormous “Pink” defect;

Till hi some secluded corner of the hostile Spanish main,

They had beached, and scraped, and caulked her, and were off to sea again.

On the anvil of their duty, Hawkyns, Frobisher, and Drake

Forged traditions of the Service for the use of Robert Blake,

Who adopted them in toto with the silence of his breed,

And bequeathed to his successors, fully proved and guaranteed.

Now, there may be “too much Nelson,” for the times have changed since then,

But as long as Man is human we shall have to count on men;

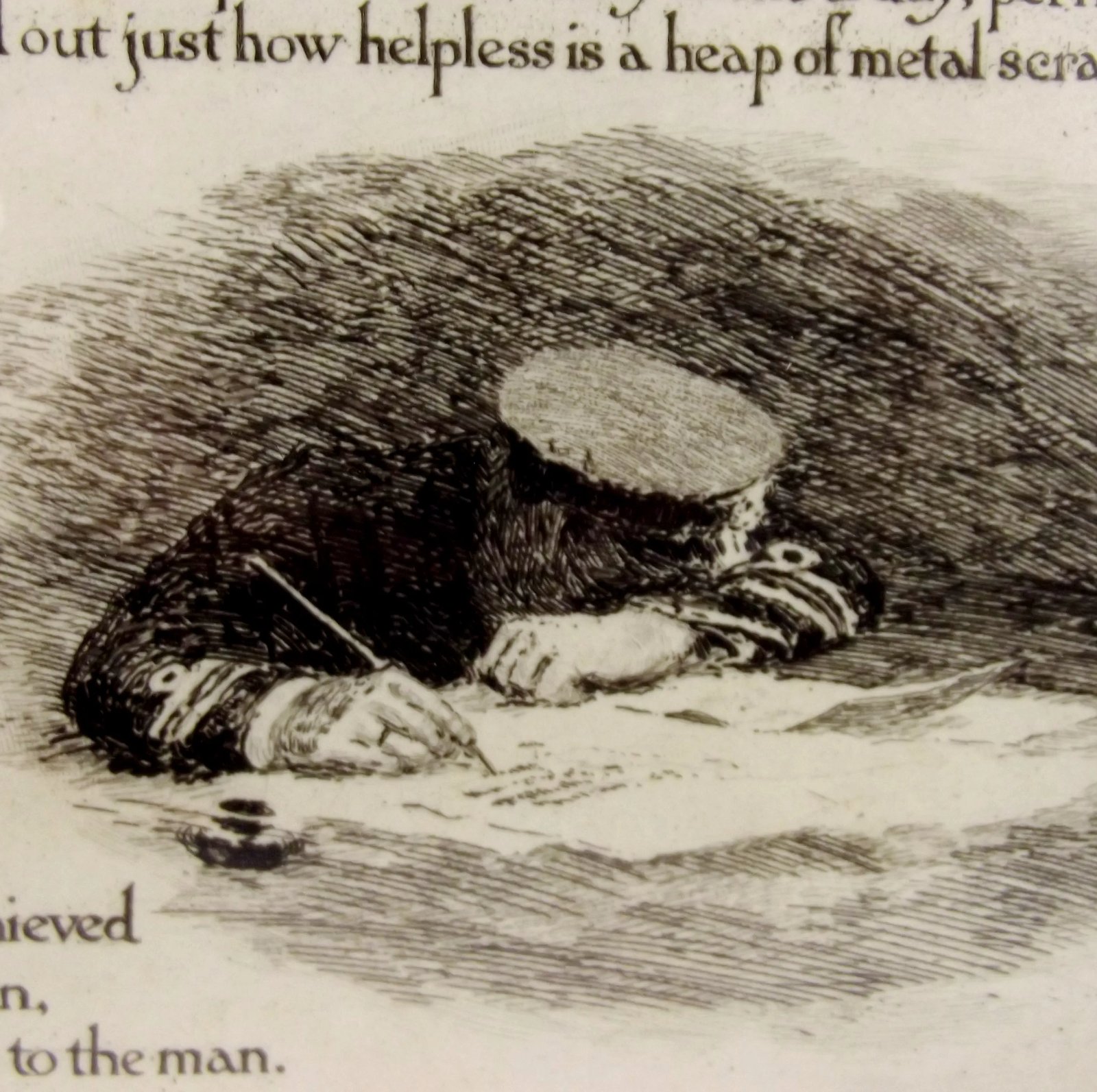

Though machines be ne’er so perfect, there may come a day, perhaps,

When you find out just how helpless is a heap of metal scraps.

So the man, machine-ly treated, and whose hopes are fast aground

In the “Proper Service Channels,” where the broken hearts are drowned,

When he’s strained will fracture badly, and be crippled, mind and limb

You may try to join the pieces, but you’ll get no help from him.

In an age of swift invention it is frequently believed

That the pressure of a button is as good as work achieved;

But the optimist inventor should remember, if he can,

Though the instrument be perfect, there are limits to the man.

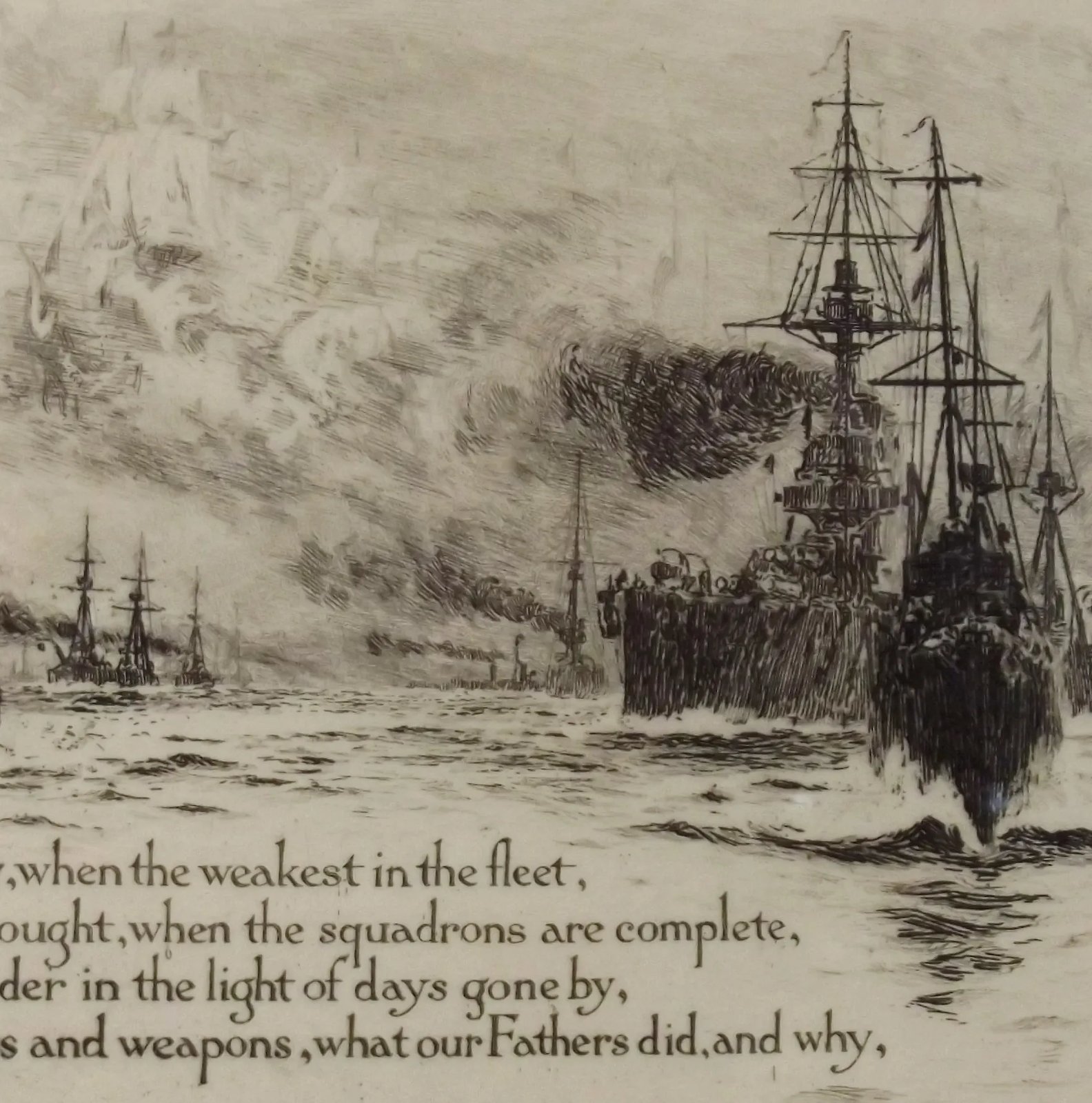

Wherefore, when we’ve raced the seagulls, run submerged across the Bay,

When we’ve tapped a conversation fifteen hundred miles away,

When the gyros spin superbly, when we’ve done away with coals,

And the’tanks are full of fuel, and the targets full of holes,

When the margin’s full of safety, when the weakest in the fleet

Is a Hyper-Super-Dreadnought, when the squadrons are complete,

Let us pause awhile and ponder, in the light of days gone by,

With their strange old ships and weapons, what our Fathers did, and why.

Then if still we dare to argue that we’re just as good as they,

We can seek the God of Battles on our knees, and humbly pray

That the work we leave behind us, when our earthly race is run,

May be half as well completed as our Fathers’ work was done.

~ William Lionel Wyllie ~

Wyllie was born 5th July 1851, in London. The British marine artist William Lionel Wyllie was the son of the artist William Morison Wyllie, and Katherine Smythe (nee Benham). Wyllie showed artistic talent from an early age. He attended Heatherley’s art school until the age of fifteen, leaving to study at the Royal Academy Schools, where he won the Turner Medal at the age of eighteen.

In the early 1870’s Wyllie became an illustrator for the Graphic. He held several exhibitions at galleries of the Fine Art Society and elsewhere. In 1889 he was elected an associate of the Royal Academy, and exhibited his work their in 1901, an event which greatly enhanced his reputation.

Wyllie spent much of his time at sea working for the White Star Shipping Line, and serving in the Royal Navy during WWI. Wyllie painted seascapes and coastal landscapes, in which his treatment of light and atmosphere was the predominant feature, bringing to the paintings a feeling of peace and tranquility. His watercolours and oils portrayed a wide range of maritime subjects, from destroyers and battleships to fishing boats and sailing dinghies. It was his etchings and watercolours showing working life on the Thames and the Medway that brought him widespread popularity.

Later in his life he played an important role in the restoration of the Victory, and this led him to paint, somewhat uncharacteristically, the 42 foot panorama of the Battle of Trafalgar, as seen from the stern of the French ship of the line Neptune. He completed the panorama in 1930 with the assistance of his daughter Aileen. Wyllie died on the 6th April 1931 in Hampstead, and scouts from the 1st Portchester Sea Scout Troop, which he had founded, rowed his coffin across Portsmouth Harbour for his burial at Portchester Castle.